How to Deal with Complexity Like a Pilot (Part 2)

Slow is Smooth. Smooth is Fast.

Slow is Smooth. Smooth is Fast.

(Only takes 10 minutes to read.)

Editor’s Note: This is part 2 of Carl Forsling's series on “How to Deal with Complexity Like a Pilot.”

Part one of Carl's article made it to the front page of Hacker News with more than 4,000 readers from 90 countries! Congratulations Carl!

You can upvote part 2 on Hacker News here.

Did you miss part 1? No problem, you can read it here.

Don't forget to

Subscribe and Share this article using the links below.

Email •

Twitter •

LinkedIn •

Hacker News •

Reddit

This free edition of Franklin Faraday Insights is sponsored by Task Force Talent, your experts in science, technology, and security careers.

Whether you are an individual seeking a new career or a company requiring special expertise, Task Force Talent will help you accomplish the mission.

Check out Task Force Talent at www.taskforcetalent.com or call toll free at (844) 930-3462. Use referral code 1000FFGOCT21 to get an extra $1000 bonus for referrals before October 31, 2021.

“A logical sequence performed

“A logical sequence performed

methodically is almost always faster

than poorly winging it and

attempting to do everything at once.”

Any complex task can be broken down into several subordinate tasks. In part one, we discussed how Aviators group these smaller tasks into buckets by order of priority: “Aviate, navigate, communicate.”

While everything must be done, if you’re too slow aviating, you’ll never get to the navigating or communicating. You may not die, but you’ll never reach your destination. You need to find ways to finish all the important tasks expeditiously.

Aviators have developed solutions to get all their tasks done by the most stringent deadline of all: time to impact.

Checklists and flows. The reason people don’t prioritize and perform tasks in a proper order is because they don’t think they have enough time to aviate, navigate, and communicate in sequence. They run out the door while jamming papers in their bags and calling on their cell phones to say they’ll be late. Invariably, they forget something important, pick the slowest way to work, and sound like fools on the phone. A logical sequence performed methodically is almost always faster than poorly winging it and attempting to do everything at once.

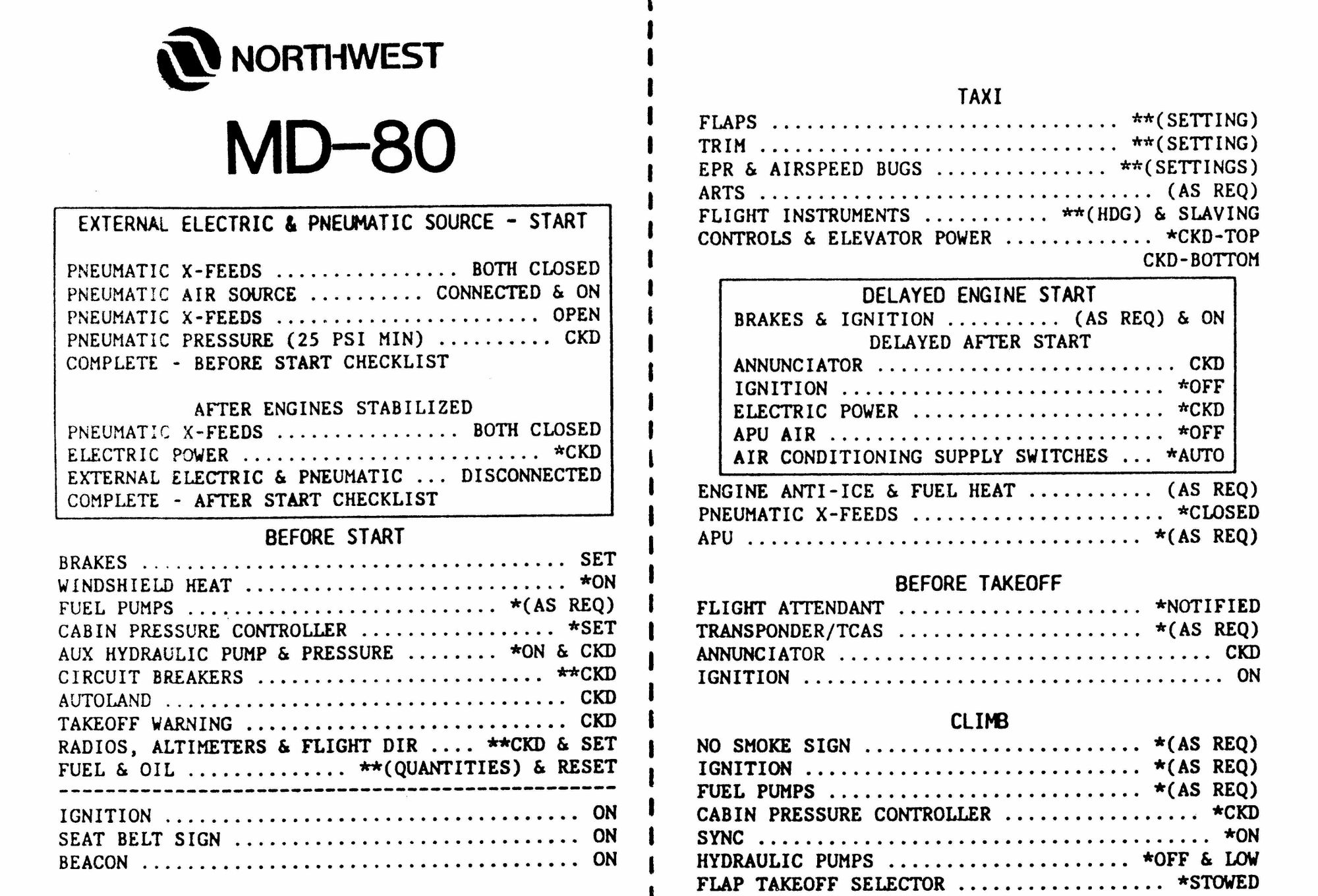

The next step requires some amount of pre-planning. Any routine task can have a checklist and/or a flow. A checklist is a set of step-by-step procedures to make sure every required element of a task is completed. In aviation, almost everything from start-up to shutdown has a checklist associated with it.

Within larger checklists, there are also sections of related items called “flows.” When I was the non-flying pilot in a V-22, after the flying pilot briefed the type of landing he would perform, I knew to check, adjust as necessary, and call out the states of the landing gear, brake, exterior lights, nose lock, and interim power. Those were the key elements of the landing checklist that needed to be performed expeditiously and accurately every time.

The most perfect approach to landing, on airspeed, on altitude, to a precise point, will end in disaster if the gear isn’t down. If you have a checklist, follow it—every time!

So too with more earthbound activities. A simple example might be in giving a presentation: how often have you seen otherwise well-prepared individuals fall apart because of a trivial A/V issue that could have easily been addressed earlier, if he or she had remembered?

A simple mental checklist can prevent a great many workplace disasters. There’s a reason that checklists have migrated from aviation to other professions with high consequences for error, such as surgery.

Methodical procedures aren’t just for routine events, either. Almost every potential emergency in an aircraft has been thought of in advance with the optimum responses devised and written in a manual.

The steps that need to be done right away from memory are called “asterisk” or “boldface” items, from the way they’re designated in the manual. They need to be done quickly to avoid violent death.

After those, the next step is to break out the book, because after you make sure you aren’t going to die in a fire, the most important thing is to not make the situation worse by missing steps, or worse, winging it.

The worse things get, the more important procedures become, not less. The plan devised by engineers in air-conditioned offices is probably better than whatever half-brained idea you come up with when your pulse rate is 180.

There’s an important saying, not just in aviation, but in the military generally. “Slow is smooth, smooth is fast.”

Many people, especially when others are watching, get more harried and more jittery as they try to do things more quickly. Their minds get scattered, their hands get shaky, and they take more time correcting their mistakes than they would have needed to do the task methodically from the beginning. This is often because the desire to appear to be acting quickly impairs the ability to actually perform a task.

Realize you’re becoming flustered and slow down. Slow your breathing, ratchet back your speed, and follow the checklist!

Repetition. Take care of the simple things, and the hard things take care of themselves. Every insurmountable task is composed of many smaller tasks. Many of those tasks can be mechanized, or at least practiced to the point to which they are second nature and no longer take up the same cognitive load.

Pilots and aircrew get the opportunity to practice these items in elaborate and increasingly sophisticated simulation devices. Still, the best military pilots spend a lot of time “chair flying” common maneuvers, especially at the beginning of their careers.

This can be as simple as sitting in a chair while gripping an imaginary throttle and stick and talking through maneuvers while visualizing them. It can be a little more complicated—in flight school, my housemates and I spray painted the Naval Air Station Corpus Christi runway diagram onto our lawn and practiced flying the pattern with the appropriate radio calls like children running around on an enormous play mat.

However it’s done, practice is critical.

Too often, we worry about practicing the most difficult aspects of any task, when in reality these parts aren’t typically the problem. How often do you spend hours making the perfect presentation slide “build,” when you could have spent that time practicing the presentation itself? It’s the “blocking and tackling,” the fundamentals, that are bungled far more than either minute details or the most complex aspects of a task.

If you practice the basic elements of a task until they are second nature, and you can perform them automatically, any elaboration on them is much easier.

Understand the fundamentals. There’s a common misunderstanding that sees modern aviation as primarily a button pushing endeavor. It certainly may appear that way looking at the top of the profession, whether that is an F-35 or a 787.

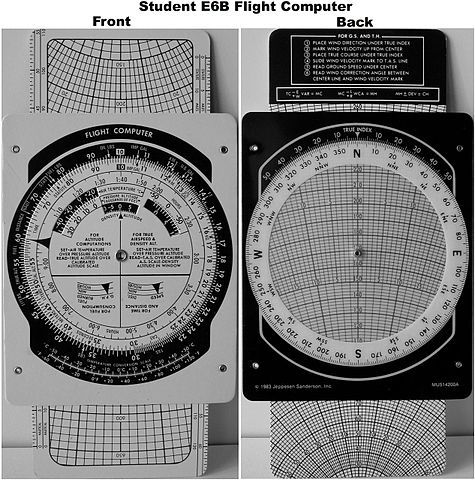

You can bet that even those pilots spent a large portion of the early parts of their careers planning their flights with paper maps, rulers, and protractors. They calculated their speeds and fuel consumption with circular slide rules called “whiz wheels.” They did their first cross-country navigation flights by steering a heading with a wind correction they manually calculated and timing the leg with a stopwatch.

Yes, all those functions can be done with an iPad or similar device today, and after one has trained for a while, it generally should be. But beginning your training by knowing and practicing the underlying principles of what you’re doing is tremendously important.

Perhaps most obviously, some amount of practice without state-of-the-art tools is important because sometimes they don’t work. Right now, the military is devoting a considerable amount of effort into relearning how to work without GPS, because it rightly assumes that a peer competitor will be able to jam or spoof signals during wartime. If someone doesn’t know the fundamentals, he will blindly trust the output of machines. While most bad outputs are usually the result of bad inputs, knowledge of manual methods is an important way to know when something is amiss—a sanity check.

Air France 447 was flying a red-eye from Rio to Paris on the evening of May 31, 2009. While a long flight, it should have been uneventful. A minor malfunction in an aircraft sensor called the pitot tube caused a cascade of failures that killed 228 people. The pitot tube, which measures the pressure of the oncoming air and thus helps compute airspeed, became covered with ice. This lack of air pressure was read by the aircraft as a rapid deceleration. The aircraft automatically deactivated the autopilot from the flight controls to allow the human flight crew to make emergency decisions.

Unfortunately, the humans did not make decisions any better than the machine. The pilots made a series of incorrect control inputs that could be summarized as pushing full power while pulling back on the control stick. Any aircraft, save those with extreme thrust-to-weight ratios, such as fighter jets, will eventually stall when faced with such conditions. The angle-of-attack, or the angle between the wing and the relative wind flowing over it, becomes so extreme that the airflow separates, the wing stops generating lift, and the aircraft plummets.

The aircraft even has a separate stall warning system to alert pilots when this might be happening, which performed as advertised. They knew they had full power in, yet their airspeed was somehow low, the were falling, AND they heard a stall warning, yet they didn’t do the first basic inputs to correct a stall that every pilot learns within the first few flights in a single-engine prop plane—reduce the angle of attack, i.e. lower the nose, level the wings, THEN add power.

Even if the pilots had forgotten those steps in from flights years ago, they should have known that if they were losing altitude with full power engaged with a high nose attitude, the only explanation was a stall.

Know the fundamentals of your equipment.

Advanced tools are best employed by those who know the principles underlying them. A computer can spit out the speed and altitude that will give the best range in a given configuration and atmospheric conditions, but it can’t balance that against the myriad other factors that a good pilot considers when planning a route, much less when things change.

Many training environments start students off using manual methods before allowing artificial assistance. You might remember having to learn basic math by hand before being allowed a calculator. Where aviation differs is that good flight instructors force their students to practice their ability to revert back to manual methods.

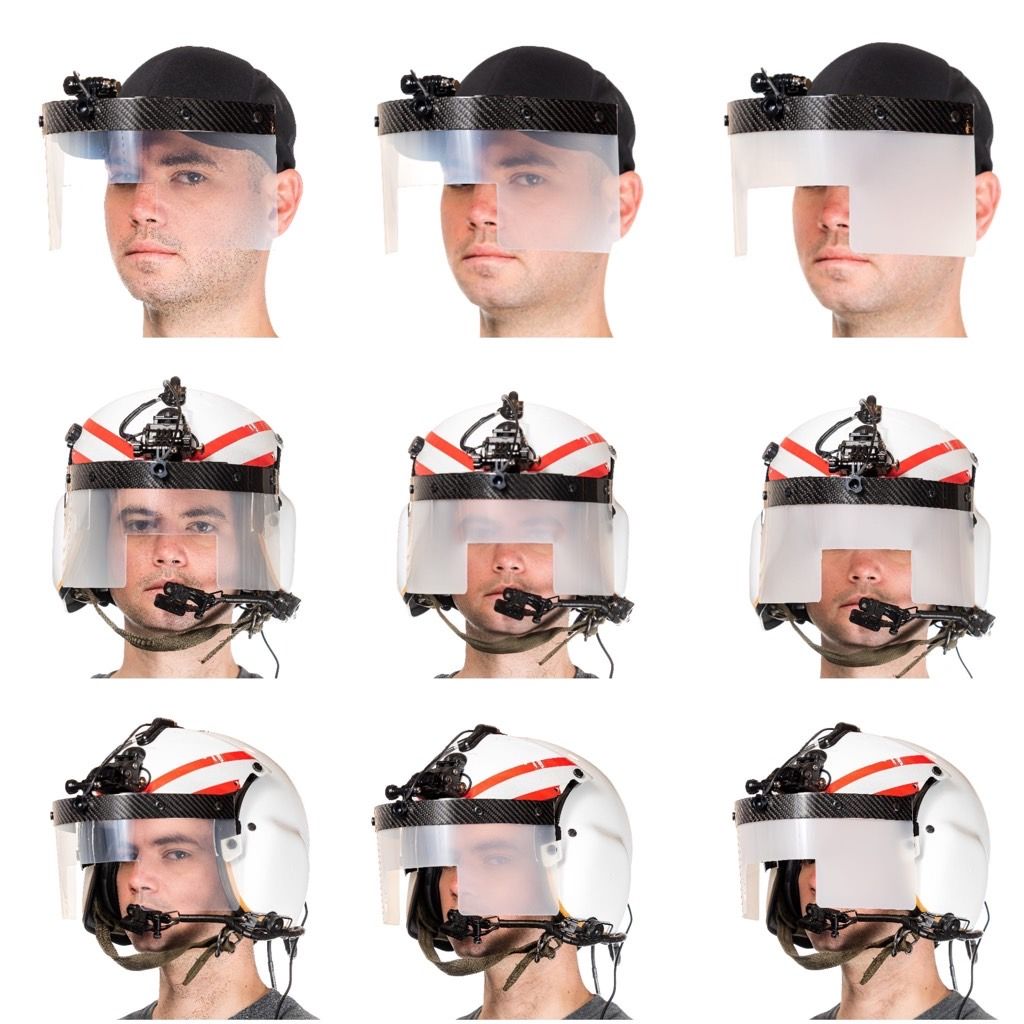

It’s not uncommon for flight instructors to force a student to practice fundamentals by turning off various systems, especially if he appears to be blindly trusting whatever the computer tells him.

To foster better airmanship, an instructor will cover up the student’s attitude gyro, which shows the orientation of the aircraft in space. This forces him to rely on secondary instruments to maintain orientation. By looking at his airspeed and vertical speed indicator, a pilot can deduce his nose attitude. By looking at his turn needle and ball, he can judge his angle of bank. To force a student to cross check his position instead of blindly following the needles on his display, the instructor will turn off the GPS.

Practicing something in a degraded environment is the best way to perform at a high level in the optimal environment. Give your talk without PowerPoint before you try it with the slides. Occasionally convert kilometers to miles without asking Siri. And try a new route to work without using Google Maps. You might find that the presentation is better when you actually speak to your audience in a conversation, or when they are looking at you instead of a screen. You might find a shortcut in rush hour that you never considered.

Early British pilot Alfred Lamplugh famously said, “Aviation is not in itself inherently dangerous. But to an even greater degree than even the sea, it is terribly unforgiving of any carelessness, incapacity, or neglect.”

Aviation is no more challenging in itself than many other fields of human endeavor, but it does give harsh feedback. The methods pilots employ to stay alive are the same ones that can help you succeed.

Don't forget to

Subscribe

and Share this article using the links below.

Email •

Twitter •

LinkedIn •

Hacker News •

Reddit

Copyright © 2021 Franklin Faraday Group LLC. All rights reserved.