How to Deal with Complexity Like a Pilot (Part 2)

Slow is Smooth. Smooth is Fast.

Job One: Don't Crash!

(Only takes 7 minutes to read.)

Editor’s Note: For more than 100 years, aviation has combined bleeding edge technology with catastrophic risk like no other field of human endeavor. While our world is now filled with complex, interconnected, ultra-high speed (and often expensive) systems, the consequences of failure vary widely.

Bankers still walk home at night after a complete system crash. Pilots do not.

Thus, we are pleased to have Carl Forsling kick off the fall season of Franklin Faraday Insights with a two-part series on “How to Deal with Complexity Like a Pilot.”

Subscribe now so you don't miss part 2!

This free edition of Franklin Faraday Insights is sponsored by Task Force Talent, your experts in science, technology, and security careers.

Whether you are an individual seeking a new career or a company requiring special expertise, Task Force Talent will help you accomplish the mission.

Check out Task Force Talent at www.taskforcetalent.com or call toll free at (844) 930-3462. Use referral code 1000FFGOCT21 to get an extra $1000 bonus for referrals before October 31, 2021.

“Unlike most other human

“Unlike most other human

endeavors,

aviation has a swift feedback mechanism for severe mistakes:

immediate violent death.”

Every new technology—from cell phones to Slack—promises more efficiency, yet it seems like our workload always increases.

For example, the chaos of a Wall Street trading floor has been replaced by the whirring fans of New Jersey data centers. In fractions of a millisecond, computers execute tasks that previously required teams of people and piles of paper. Even so, modern securities traders are hardly known for their sloth-like lives of indolence.

While technological complexity has increased exponentially, human capability has not. Your gray matter is no different than that of your predecessors 50 or 100 years ago. While you may be more psychologically accustomed to a higher cognitive load, physiologically you are no better suited to it than your Industrial Age—or perhaps Iron Age—peer.

High levels of complexity combined with high levels of stress increase the risk of serious errors. Several months or years may pass before investment mistakes become apparent. Unlike most other human endeavors, aviation has an swift feedback mechanism for severe mistakes: immediate violent death.

Just as in other areas of life, technology has made specific tasks in aviation easier while increasing the overall cognitive ability expected of individuals.

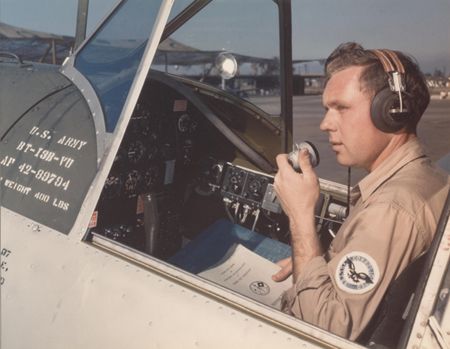

Compare a World War II P-38 Lighting fighter pilot with the pilot of its modern namesake, an F-35 Lightning II fighter jet. The P-38 pilot had to navigate darkness and bad weather with only rudimentary instruments and navigational equipment that wouldn’t even be legal today. This was undeniably difficult.

Yet, while the F-35 pilot can penetrate bad weather without hesitation, the job—as a whole—is far more complex. The F-35 pilot must manage his own phased array radar, the information ported into his helmet from a data link with his wingmen, and images from a distributed aperture system that provides a 360 degree view around the aircraft.

“Having the most

“Having the most

advanced aircraft in the world is worthless

if it hits the ground.”

The pilot of an F-35—and any other modern plane—stays alive by prioritizing tasks in a very specific way: Aviate. Navigate. Communicate.

“Aviate” means doing those things necessary to keep the aircraft flying before taking care of anything else. Helicopter pilots call it “keeping the rotor side up and the wheels side down.” Having the most advanced aircraft in the world is worthless if it hits the ground.

“Navigate” means ensuring that you are traveling at the right course, speed, and altitude. For all the missions that aircraft do, in the end, they all pretty much come down to being in the right place at the right time. That means arriving at the assigned gate at LAX on schedule or dropping a bomb on the right grid position at the right moment.

“Communicate” is telling others what is going on. Sometimes it’s mandatory, other times it’s not. At no time is it more important than aviating or navigating.

“…in most cases the only thing shouting “Mayday! Mayday!” does is get the airport fire trucks ready to hose down the flaming wreckage containing your corpse.”

“…in most cases the only thing shouting “Mayday! Mayday!” does is get the airport fire trucks ready to hose down the flaming wreckage containing your corpse.”

Pilots know that no one else can help them fly their aircraft in an emergency. Sometimes air traffic control can help clear other aircraft out of the way. However, in most cases the only thing shouting “Mayday! Mayday!” does is get the airport fire trucks ready to hose down the flaming wreckage containing your corpse.

“But I’m not a pilot!”

These steps all have analogues in most complex business and personal tasks.

“Aviate” is the actual execution of our plans. It includes those tasks that keep you from being fired or keep you or your family from death or injury—the “what needs to be done right now.” If you’re driving your car, these tasks include not hitting anything, entering turns at a safe speed, and turning the wheel to end up in the correct lane.

“Navigate” means those things that set your longer-term course towards your professional or personal mission. It’s determining your current position, comparing it to where you should be, and adjusting accordingly. You should be cross checking this as often as possible and bringing in additional information when available. Just like a pilot updates the weather during a flight, you need to periodically refresh the assumptions you made when planning.

Some of these adjustments may be for checkpoints five seconds away and some for destinations five years from now. You may have just spotted a prominent person in your field at a professional event and need to plan your elevator pitch in your mind in the next few minutes. You may be planning your retirement and have a few years. Both require you to regularly cross check your actual position against your intended position and make timely adjustments.

“Communicate” is about telling people what you’re doing. This could be informing senior managers of the situation, or it could just be calling ahead to let people know you’re late. Whatever it is, make sure you ask yourself, “Is this communication going to help me accomplish my mission?” and then, “Do I need to tell someone right now?”

These things happen in a continuous loop until you reach your ultimate destination. Take action, check your progress, and tell the people who need to know. Repeat.

"Never drop the airplane

"Never drop the airplane

to fly the radio."

Priorities. Hitting the ground is what we’re always trying to avoid, both in flying and in life. If you are truly in extremis, then you have to do what you have to do. Even in our daily tasks, though, are we really making the main thing the main thing? Are we just doing the next thing on our list, or worse, “multitasking?”

Aviating is always the top priority, but if all we do is avoid the ground, then eventually we run out of gas without actually getting anywhere. There is always one more important task to do. All to-do lists are inherently self-refreshing. What we can do is space those tasks out so that we do the right tasks at the right times.

We cross check our position only after we know the aircraft is safely under control. We address communication only after we make sure we’re headed in the right direction.

Pilots take an action, set the right course for the destination, and only then tell whoever needs to know about it. People can’t actually multitask. They can really only microtask. Always defer non-time-critical items to when you aren’t task saturated.

Roll out of your turn and check your heading and altitude. Then make sure you’re where you’re supposed to be and make (hopefully small) adjustments. Only then should you worry about telling anyone else about what’s happening. Trying to communicate while making a turn will only ensure that both the comms and the maneuver get screwed up.

Too often people elevate communication to a higher priority than it really is. Most people waste incredible amounts of time “statusing” people who can’t actually help. Other times, it’s self-induced pain—texting and emailing people as work-signaling, or even worse, excessive posting on social media. Never drop the airplane to fly the radio.

If you live the maxim, “aviate, navigate, communicate,” you’ve already improved your ability to accomplish your missions in business and life. That said, if you cannot perform the aviation tasks quickly enough to allow time for the navigation, then you’ll still never get to where you’re going.

Even as we try to minimize communication, some of it is still important—air traffic controllers get hopping mad if you land without clearance. The next step is to increase the speed of our aviation, navigation, and communication while still prioritizing them correctly.

Don't forget to

Subscribe

and Share this article using the links below.

Email •

Twitter •

LinkedIn •

Hacker News •

Reddit

Copyright © 2021 Franklin Faraday Group LLC. All rights reserved.